Anaktoro Archanon: The Minoans Protected It from Natural Disasters

Author Discover Crete

Culture

Culture

A rather unconventional architectural choice by the Minoans — unusual given how carefully they usually built — but ultimately a testament to their technical genius, came to light during the 2025 excavation at the Palace of Archanes.

Under the direction of Dr. Efi Sapouna‑Sakellaraki, the archaeological work (actually restarted) in 2023 aimed to complete our understanding of the three‑storey main building of the Archanes palace, which flourished, in the form recently revealed, until about 1450 BC.

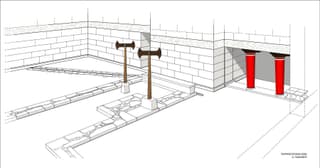

This year’s excavation focused on a slanted, double wall that had strangely closed off a large part of the palace courtyard — built not with refined masonry but with raw, unworked stones. Such a construction raised many questions. But through systematic archaeological study and specialist input, it was shown that the wall was intentionally built to protect the building from natural disasters, especially from rock‑slides from the overhanging cliff. That’s also why the southern face of this wall remained unfinished — it was not visible externally.

Still, the Minoan architects’ taste and skill would not allow such a crude external face. So they built a second, visible wall attached to the first, facing the courtyard. This second wall is finely constructed from neatly cut porous‑stone blocks, identical with the stones used in the rest of the palace.

Above this wall archaeologists found layers from the later Mycenaean period, with many kylikes (drinking cups) and other historic‑period finds. Evidence of continuous use of the space over time includes finds from the Hellenistic period — for example, a trefoil‑mouth oinochoe decorated with two relief heads (3rd century BC) and a clay head that was likely attached to some object.

Significant discoveries also emerged in the southeast part of the excavation. In “Area 28,” archaeologists unearthed an opening from the central court toward the palace’s easternmost section, divided by stone slabs into two zones. On top of these slabs lay a large trapezoidal stone with tenons — suggesting the presence of a parapet, later destroyed by a Mycenaean‑era wall. A natural stone bearing anthropomorphic features was also found here — apparently fallen from an upper floor — possibly part of a “fetish shrine” akin to the one at Knossos.

Overall, the 2023–2024 excavation seasons have yielded important new evidence about the palace’s function. In the northernmost area revealed so far, archaeologists uncovered two‑ and three‑storey rooms — an elite wing of the palace: luxurious chambers connected by corridors, plaster‑clad with gypsum‑stone pilasters, fragments of frescoes, walls coated with fine mortar, floors of schist slate, and more. In many rooms the familiar partition/mortar bands encircling floor slabs remain in place.

The Palace of Archanes stands in the heart of today’s town, in the area known as “Turkogeitonia.” It was destroyed by an earthquake around 1700 BC but rebuilt, flourishing until around 1450 BC when it suffered its final destruction. The excavations revealed that use of the site continued without interruption.

First mention of Archanes came from Sir Arthur Evans due to significant finds (most of which are now in the Ashmolean Museum), apparently from the Minoan cemetery on Fourní hill — later excavated by Giannis and Efi Sakellaraki, yielding five tholos tombs, many funerary buildings and Mycenaean chambered tombs. In the town itself, Evans noted the remains of large walls and excavated a circular aqueduct in an area associated with the palace. Later, Giannis Sakellaraki’s survey and investigations of basements beneath modern houses in the town centre showed they rested upon strong Minoan walls — something many earlier researchers (such as Marinatos and Platon) did not recognise despite their efforts to locate Evans’s “summer palace” according to Victorian‑era theories. They had been looking in areas outside the real palace grounds.

Thanks to Sakellaraki’s mapping of all these remains, researchers pinpointed the centre of the Palace of Archanes — yielding plenty of architectural and luxury movable finds. Nearby they also discovered the archive and a theatre belonging to the palace.

The 2025 excavation was carried out by the Archaeological Society and once more featured a skilled team: archaeologists Dr. Polina Sapouna‑Ellis, Dimitris Kokkinakos (MA) and Persephone Xylouri, draftsman Agapi Ladianou, restorer Beta Kalyvianaki and photographer Kostas Maris — with special contribution from Dr. Charalambos Fasoulas in clarifying the role of the palace courtyard’s “slanted wall.”

The inclusion of Zominthos — discovered on Psiloritis by Giannis Sakellaraki and excavated with Efi Sapouna‑Sakellaraki — into the UNESCO World Heritage List recognises not only the uniqueness of that monument but broadly highlights the value and Minoan identity of Crete. In the archaeological site and surrounding area improvements were made: parking facilities, guard post, toilets, informational signs, and more. The inclusion took place along with other major Minoan palaces such as Knossos, Phaistos, Zakros, Malia and Kydonia.

It should be noted that small museums/information centres have been established in both Archanes and Anogeia — solely dedicated to the finds from excavations at Archanes, Zominthos and the Idæan Cave respectively.